Increasing the effectiveness of cities’ circular economy efforts

Overconsumption of natural resources increases biodiversity loss and global warming, and is the root cause of the necessity of transitioning to a circular economy (e.g. Nikula 2022). Our current linear economic system has enabled and even encouraged economic growth through the overconsumption of natural resources at the expense of future generations. A systemic change in the way we operate is necessary from the point of view of the very existence of our civilization.

Recycling waste is not a sufficient circular economy measure; instead, every process in society must be examined from the perspective of the circular economy and successful circular economy pilots must be established as part of basic operations. Strengthening life cycle thinking is an important part of the transition to a circular economy. The operating models that are cheap today, but increase the costs to future generations, must be abandoned as quickly as possible. Municipalities must therefore also review their readiness to extend the payback periods of investments and to accept a higher investment cost at the time of acquisition if, according to environmental impact assessments, the project will achieve significant life cycle benefits and lower life cycle costs (Myllymaa et al. 2022).

The circular economy is still young as an academic concept, but research around it is developing strongly (Vanhamäki 2021). Circular economy measures are often described with the help of the butterfly diagram prepared by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, in which the effectiveness of the measures increases as you move towards the inner loops (Myllymaa et al. 2022). For example, reusing materials for their original purpose is an inner loop than recycling, and maintaining and sharing items, in turn, is an inner loop than reusing material.

Some experts even consider ecological sustainability to be a prerequisite for achieving economic and social sustainability (e.g. Levett 1998, cited in Vanhamäki 2021). Recently, people have started talking about doughnut economics. According to this approach, development is sustainable only if human well-being is achieved within the limits dictated by the sufficiency of natural resources and the functioning of ecosystems. In doughnut economics, the economy is understood as a tool for achieving social and environmental goals. For example, a small municipality with a shrinking population, but implementing a lifestyle close to nature, can do better when measured by the metrics of doughnut economics than a big city with a higher standard of living, but accelerating consumption. In this case, well-functioning basic services and other structures of the welfare society enable the well-being of the residents regardless of their income level. (University of Jyväskylä 2022.)

Applying the doughnut economics model at a local level is in its early stages. However, Amsterdam has made use of the model as a pioneer, and Copenhagen has also decided to draw up a plan for applying the model in its own operations. In the Tampere region, the tool has been used to assess ecological and social sustainability. (Doughnut Economics Action Lab 2022.) In Jyväskylä, a Finnish-language tool has been prepared for creating a city portrait in line with the model. (University of Jyväskylä 2022.)

Municipalities have called for specifics and evidence with regard to the most effective circular economy measures (e.g. Antikainen et al. 2022) and the ideological nature of the circular economy has also been criticised from time to time (e.g. Satuli 2019). Challenges in measurement and the lack of common goals and indicators for municipalities make it difficult to identify the most significant measures in terms of the big picture, especially at regional and city level (Metsänranta & Weckman 2021; Antikainen et al. 2022). However, this should not hinder the implementation of measures aimed at stopping the overconsumption of natural resources. According to the precautionary principle, efforts must be made to prevent the risks of environmental pollution even if there is no full certainty about the nature and extent of the harmful environmental impacts.

Cities are hubs of consumption

Cities are hubs of consumption, but on the other hand, the various resources required by solutions are also concentrated in cities (Jokinen 2021). According to the vision of Finland’s road map to a circular economy 2.0, in 2025, cities will activate and encourage enterprises, communities and residents operating in their area to participate in the circular economy. Cities will serve as, for example, strategic leaders, land use planners, buyers, customers, investors, property developers, licensing authorities, waste and energy management operators and educators, and they can contribute to the circular economy in all these roles. (Myllymaa et al. 2022; Sitra 2019.)

One of the most important circular economy measures in cities is promoting circular procurement, which sets an example for other operators and, above all, strengthens the circular economy market (Jokinen 2021; Vanhamäki 2021). Circular economy pilots actively developed and implemented by cities can also stimulate and promote, for example, business renewal, sharing economy solutions, creative civic activities, reuse of spaces and social innovations (Ritschkoff & Schönach 2021; Myllymaa et al. 2022).

Despite the circular economy measures already taken, even pioneer municipalities have challenges in implementing the transition to a circular economy (Antikainen et al. 2022, Jokinen 2021). It is therefore important to share the lessons learned from circular economy examples and case studies. Although there are rarely solutions whose results can be applied to all cities and regions with certainty, the examples serve as inspiration and encourage others to take action (Vanhamäki 2021).

General recommendations for cities to promote the circular economy

Maintain a mindset in which the city is part of a larger whole

In order to successfully implement the circular economy, it is necessary to maintain a holistic and global perspective. The chains of impact almost always extend beyond one region or city. Efficiency and success in one area can thus lead to problems elsewhere, which highlights the importance of global systemic understanding. (Vanhamäki 2021.)

Incorporate the circular economy into the city’s operations

The circular economy can be viewed as a development path that offers urban development a completely new way of combining the city’s industrial and environmental policy objectives (Jokinen 2021). The main focus can also be on reconciling environmental and social policies according to the doughnut economics model.

The circular economy must be included in the city’s strategy, be visible as management commitment and cut across sectors. The implementation requires an established continuum, which means that chained funding applications and pilots alone are not enough. (Antikainen et al. 2022.) One concrete way to strengthen the implementation is to allocate resources to a circular economy coordinator who ensures that the circular economy is taken into account in the various administrative processes and in the early planning of investments and decisions (Myllymaa et al. 2022).

Divide the change into parts and identify the region’s special characteristics

As the transition to a circular economy involves a major systemic change, it is necessary to divide the change path into phases and sub-objectives by sector. In Finnish cities, the most commonly listed sectors of basic circular economy operations are industrial symbioses & circular economy hubs, sharing economy, food, construction, urban development projects and soil recycling. In addition to basic operations, cities must identify their own specific circular economy potential, which is strongly linked to the characteristics of the region; the economic structure, competence and the most significant material flows in the area. Cities should have a circular economy road map identifying their specific circular economy potential, setting goals, agreeing on implementation responsibilities and programming the implementation according to the latest information available. (Jokinen 2021.) For tips on drawing up an action programme to support the strategy, see e.g. this guide.

Keep programmes up to date

The implementation and monitoring of circular economy action plans can be perceived as challenging in cities and regions due to, for example, too cursory targets and measurement methods that are still in the development phase (Vanhamäki 2021). For the time being, the circular economy ship will have to be sailed while it is being built. However, research data is currently being updated at a rapid pace, so it is also necessary to ensure that road maps and action programmes are up to date (Jokinen 2021).

Enable the circular economy in urban planning

In land use planning, it would be most useful to take the circular economy into account as early as possible in the planning. For example, good experiences have been gained in regional planning on locating large-volume industrial operations, such as circular economy centres, in a logistically reasonable manner and taking into consideration other forms of land use. However, clear and uniform guidelines and criteria should first be drawn up regarding activities suitable for planning areas marked for the circular economy. At the master plan level, it is possible to influence, for example, the sustainable management of land masses by enabling intermediate storage areas and identifying final disposal sites. However, the most important planning level for promoting circular economy solutions is the city plan, in which the circular economy can be promoted with either indicative or prescriptive measures, incorporating circular economy requirements in, for example, building instructions and plot assignment stipulations. (Myllymaa et al. 2022.)

Implement circular public procurement

Cities can contribute, for example, by adopting solutions from the sharing economy in their own procurement or by making their own resources and information available for open use. Especially in larger cities, sharing economy solutions and business related to housing, accommodation and car sharing methods in particular have quickly become more common. (Myllymaa et al. 2022.)

Circular procurement often requires market knowledge and dialogue. Maintainability, adaptability, reusability, recyclability and harmlessness can be favoured in material choices and procurement criteria. Many procurement criteria that promote sustainability (such as the EU GPP and ecolabel) also promote the circular economy. Public bodies can also pilot the use of new materials, such as recycled textile fibres, and thus provide important reference points for circular economy operators. (Alhola et al. 2022.)

Circular procurement should start from the procurements that consume a lot of natural resources, have a high environmental impact and whose production has the greatest potential for improving material efficiency (Myllymaa et al. 2022). The scarcity of the material is also a good reason to look for a circular economy solution. Industries that consume natural resources include the construction sector, process industry, food chain and mobility (Myllymaa et al. 2022). The products and value chains defined as the most critical in terms of the sustainability challenge include electric and electronic equipment, batteries and vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, buildings, food products, water and nutrients (European Commission 2020). In the end, however, sustainability must be the basis of all procurement (Myllymaa et al. 2022). Peer learning between different procurement units is important. (Alhola et al. 2022.)

Read more (in Finnish)

- Kiertotaloushankintojen käsikirja (Circular procurement handbook), includes e.g. procurement examples and a framework of perspectives to support the impact assessment of procurement (p. 28–30) as well as tips for preparing for procurement and procurement criteria (p. 39–41).

- Circular economy in the built environment, a guide

- Use of wood in public construction: procurement guide

- Demolition work – a guide for operators and contractors

- Circular economy in public demolition projects: Procurement guide

- Kiertotalouskriteerit rakentamisen hankinnoissa (Circular economy criteria in construction procurement)

- Procurement guide for responsible food services

- Kuntien hankinnoilla hiilineutraaliuteen -politiikkasuositus (Carbon neutrality through municipal procurement, a policy recommendation)

Maintain cooperation and innovation capability

The regional promotion of the circular economy is often included as part of a smart specialisation strategy, for example, and innovation capability is also considered a key factor in finding circular economy solutions. The public operator responsible for implementing the strategy (e.g. the administration of the city or region) can create a good foundation for innovation capability by accelerating cooperation between companies, research institutes and residents towards circular economy solutions. (Vanhamäki 2021.)

Identifying and involving the right stakeholders in the planning and implementation of the transition to a circular economy is important to ensure effectiveness. A top-down approach helps in identifying the sectors to be prioritised, but the most relevant grassroots actors must also be involved in the preparation of road maps and action plans, for example. (Vanhamäki 2021.)

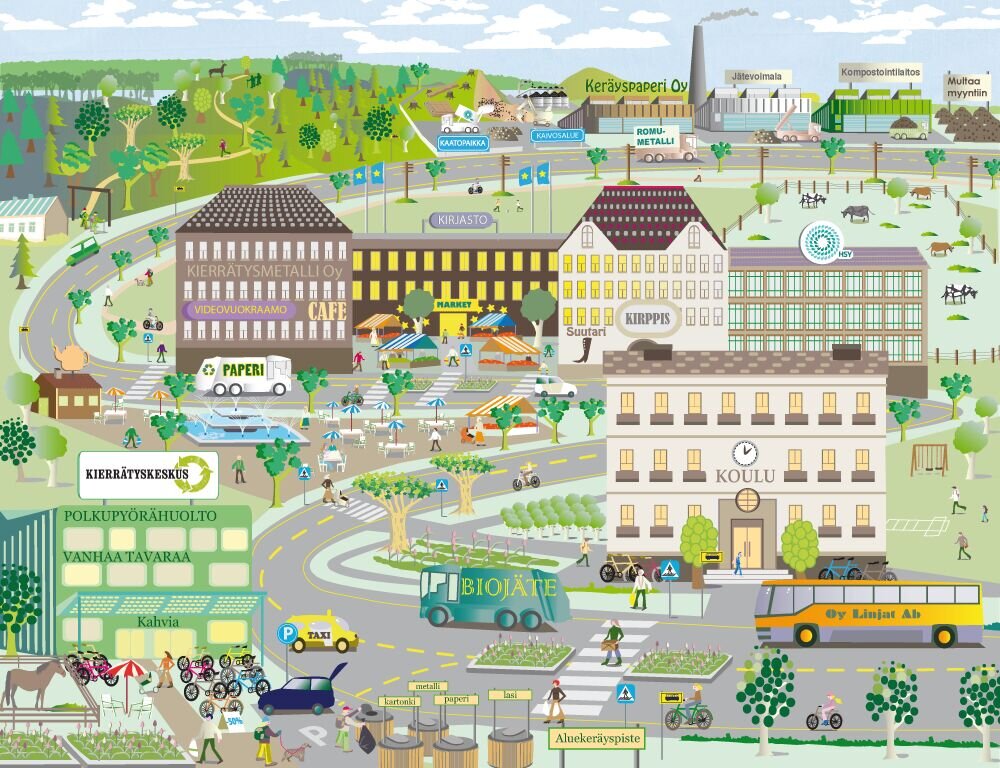

Provide residents with information, education and circular economy services

A change in consumption habits is a necessary part of transitioning to a circular economy, which is why communication and education aimed at the city residents take on an important role (Vanhamäki 2021). Municipalities must share information with their residents as well as involve and commit the residents to the transition to a circular economy. The sharing economy can be made familiar to municipal residents by expanding the activities of libraries. The municipality can also share information about available lending and repair services. (Myllymaa et al. 2022). For example, the cities in the Helsinki metropolitan area have included more than 300 circular and sharing economy services on their joint service map, all of which can be found with one search term. Municipalities can also expand the theme of sustainable consumption in early childhood education and schools. Material to support this is provided by, for example, Sitra, Motiva and HSY.

Implement tools

Projects and project funding can be used as tools to support the implementation of the strategy, such as to organise practical pilots, to facilitate the preparation of the strategy process or to maintain international cooperation (Vanhamäki 2021). Voluntary agreements, such as Green Deals, offer cities the opportunity to promote the circular economy and receive, for example, guidance from national-level experts. The green factor tool, in turn, facilitates the reconciliation of circular and nature values in city planning (Myllymaa et al. 2022).

Information about funding opportunities and tools in the circular economy is provided by, for example, the comprehensive website of Circular Economy Finland.

Benchmark, network and communicate actively

Cities should be aware of the kinds of solutions that have been implemented in other cities of the same type and also strive for joint development projects with similar cities. To this end, it is good for cities to participate and communicate about their own actions in networks in the field and to ensure that the right people are involved in the networks (Antikainen et al. 2022). At the national level, good practices are shared, for example, through the municipal circular economy action competition and the Circular Economy Finland network. KEINO Competence Centre helps with the development of procurement competence within the themes of sustainability and innovation as well as provides procurement units with examples of international procurement experiences. International networking is also important. The European Union’s Circular Cities and Regions Initiative (CCRI) aims to increase synergies among projects and initiatives, disseminate relevant knowledge and give greater visibility to best practices. Uusimaa is involved in the initiative as a pilot region.

Engage in regional cooperation as well

Regional cooperation in circular economy measures can make it possible to centralise the required investments. The consumption of natural resources is regionally differentiated, which increases the importance of broader regional objectives and defining the division of work and burdens. A lot of support material as well as exchange of information and experiences are also required for the work done to change attitudes, for example. (Antikainen et al. 2022.)

The functions centralised to HSY in the Helsinki metropolitan area, such as municipal waste management and the related advisory services for residents as well as information production on the circular economy, are good examples of regional circular economy cooperation. HSY has also led the development of the SeutuMassa tool for the regional coordination of cities’ land masses and the preparation of the joint Sustainable Urban Living Programme for the region. The programme has identified potential future projects in different sectors of the circular economy, for example. The background has been the need to avoid divergent practices and administrative criteria related to the introduction of new operating models within the metropolitan area, which could cause conflicts that slow down sustainable business and consumption (HSY 2021).

Aiming for a circular Helsinki metropolitan area, where are we now?

The cities in the Helsinki metropolitan area are already committed to promoting the circular economy at the strategic level. Helsinki aims to operate in a carbon-neutral circular economy by 2050 (Helsinki’s carbon neutrality goal is on a faster schedule, by 2030) and Vantaa’s objectives include the sustainable use of natural resources as well as being a promoter and implementer of the circular economy in 2030. Espoo is preparing a circular economy road map in late 2022, and Kauniainen outlines that in 2035 the use of natural resources will be guided by a culture of sharing and circular economy. Espoo and Helsinki have also committed to the Europe-wide circular economy commitment Circular Cities Declaration. The strategies, road maps and commitments contain numerous themed and at least partially scheduled sub-objectives and measures with monitoring tools. Common themes found in the strategies and commitments include construction, public procurement, the sharing economy and (with the exception of Kauniainen) circular economy business.

The will, initial plans and monitoring tools for measures to promote the circular economy already exist in the Helsinki metropolitan area. The cities and regional operators have implemented concrete measures, such as pilot projects promoting the circular economy. Additionally, for example, Vantaa was awarded for the best commitment to sustainable development in 2022 (including e.g. the sustainable demolition Green Deal) and Helsinki and Espoo are pioneers in joining the voluntary circular economy Green Deal, which aims to find the most effective measures to promote the circular economy together with experts and research institutes. Helsinki, Espoo and Vantaa have also been involved in steering the launch of the Helsinki-Uusimaa Circular Valley initiative.

In its new strategy, HSY aims for an even more active role as a regional coordinator and developer as well as in influencing through information with regard to the circular economy, meeting the needs of its member cities. The goal is to strengthen the region’s circular economy both by improving the efficiency of HSY’s own processes and by promoting regional cooperation. The Helsinki metropolitan area is a growing metropolis with a population of 1.2 million and, from the point of view of residents and businesses, a joint operational area that offers a good platform for e.g. circular economy pilots and business (HSY 2021).

On a general level, it can be seen that cities need increasingly accurate city-specific information in order to know which of the matters under the city’s own decision-making power should be prioritised and resourced. On the other hand, there is also a need for regional information production and cooperation in order to join forces and create sensible entities to promote the circular economy.

Regional cooperation is based on finding a common vision. It would be important to ensure that the cities in the Helsinki metropolitan area interpret the most central concepts congruently, and to identify the cities’ key common goals as well as the indicators and tools that support those goals. As common interests and priorities become clearer, it will be possible to make more efficient use of resources through regional cooperation and peer learning between the cities. Closer cooperation could be useful, for example, in the preparation of effectiveness evaluations for circular economy measures, in the drafting of uniform procurement criteria and in the further development and scaling of pilots.

References

Ahola, A., Alarotu, M., Antikainen, M., Honkatukia, J., Järnefelt, V., Kapanen, J., Lantto, R., Laurikkala, M., Naumanen, M., Orko, I., Ritschkoff, A., Still, K., Sundqvist-Andberg, H., Tenhunen, A., Wiman, H., Winberg, I. ja Åkerman, M. 2020. Kiertotalouden ekosysteemit. Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriön julkaisuja 2020:13. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/162083

Alhola, K., Lankiniemi, S., Popova, M. & Yliruusi, H. 2022. Kiertotaloushankintojen käsikirja. https://issuu.com/suomenymparistokeskus/docs/circwaste_kiertotaloushankintojen_k_sikirja_18.5.

Antikainen, J., Manu, S., Laiho, A., Berninger, K., Tynkkynen, O., Leskinen, R., Lahtela, A. 2022. Esiselvitys kuntien kiritysvälineistä ilmasto- ja kiertotaloustoimiin. Ympäristöministeriö. MDI, Tyrsky-konsultointi ja Valonia.

Doughnut Economics Action Lab 2022. https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/1; https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/4; https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/168

Euroopan komissio 2020. KOMISSION TIEDONANTO EUROOPAN PARLAMENTILLE, NEUVOSTOLLE, EUROOPAN TALOUS- JA SOSIAALIKOMITEALLE JA ALUEIDEN KOMITEALLE Uusi kiertotalouden toimintasuunnitelma Puhtaamman ja kilpailukykyisemmän Euroopan puolesta. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0021.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

HSY 2021. Kestävän kaupunkielämän ohjelma. https://julkaisu.hsy.fi/kestavan-kaupunkielaman-ohjelma-1.html

ICLEI Circulars 2022. https://circulars.iclei.org/update/five-steps-to-achieve-circularity-in-cities/

Jokinen, A. 2021. Kiertotalous kaupungin menestystekijänä. CICAT2025 politiikkasuositus. https://www.aka.fi/globalassets/3-stn/1-strateginen-tutkimus/tiedon-kayttajalle/politiikkasuositukset/politiikkasuositukset/21_05_kiertotalous_kaupungin_menestystekijana.pdf

Jyväskylän yliopisto 2022. Donitsitalous. https://www.jyu.fi/fi/tutkimus/wisdom/donitsitalous

Nikula,T. 2022. Esitys Kiertotalous-Suomen lanseeraustilaisuudessa 27.9.2022 https://kiertotaloussuomi.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/KiSu-lanseeraus-Taina-Nikula.pdf

Metsänranta, N. & Weckman, A. 2021. Kiertotalouden seudullinen mittaaminen on tärkeää mutta haastavaa. HSY:n tietoartikkeli. https://www.hsy.fi/ilmanlaatu-ja-ilmasto/kiertotalouden-seudullinen-mittaaminen-on-tarkeaa-mutta-haastavaa/

Myllymaa, T., Savolahti, H., Karppinen, T.K.M., Pitkänen, K., Salmenperä, H., Alhola, K., Vierikko, K., Silvonen, E., Seppälä, J. 2022. Kiertotalous kunnissa. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/346166/Circwaste-raportti_Kiertotalous-kunnissa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ritschkoff & Schönach 2021. https://ratkaisujatieteesta.fi/ymparistonmuutos-ja-luonnonvarat/kaupungeilla-on-keskeinen-rooli-kiertotaloudessa-ja-ilmastonmuutoksen-hillinnassa/

Satuli, H. 2019. MustRead. https://teknologiateollisuus.fi/en/node/24524

Sitra 2019. https://www.sitra.fi/artikkelit/kunta-mahdollistaa-tarkeat-siirrot-kiertotaloudessa/

Vanhamäki, S. 2021. Implementation of circular economy in regional strategies https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/163547